• The Man, The Cars, The Legend

• Why invest in Classic Cars?

The Wall Street Journal, September 17, 2004

• Customized Cars, Hot rods North America BOOM!!!!

The McKinsey Quarterly, 2005 Number 3

The hottest 25 collector cars

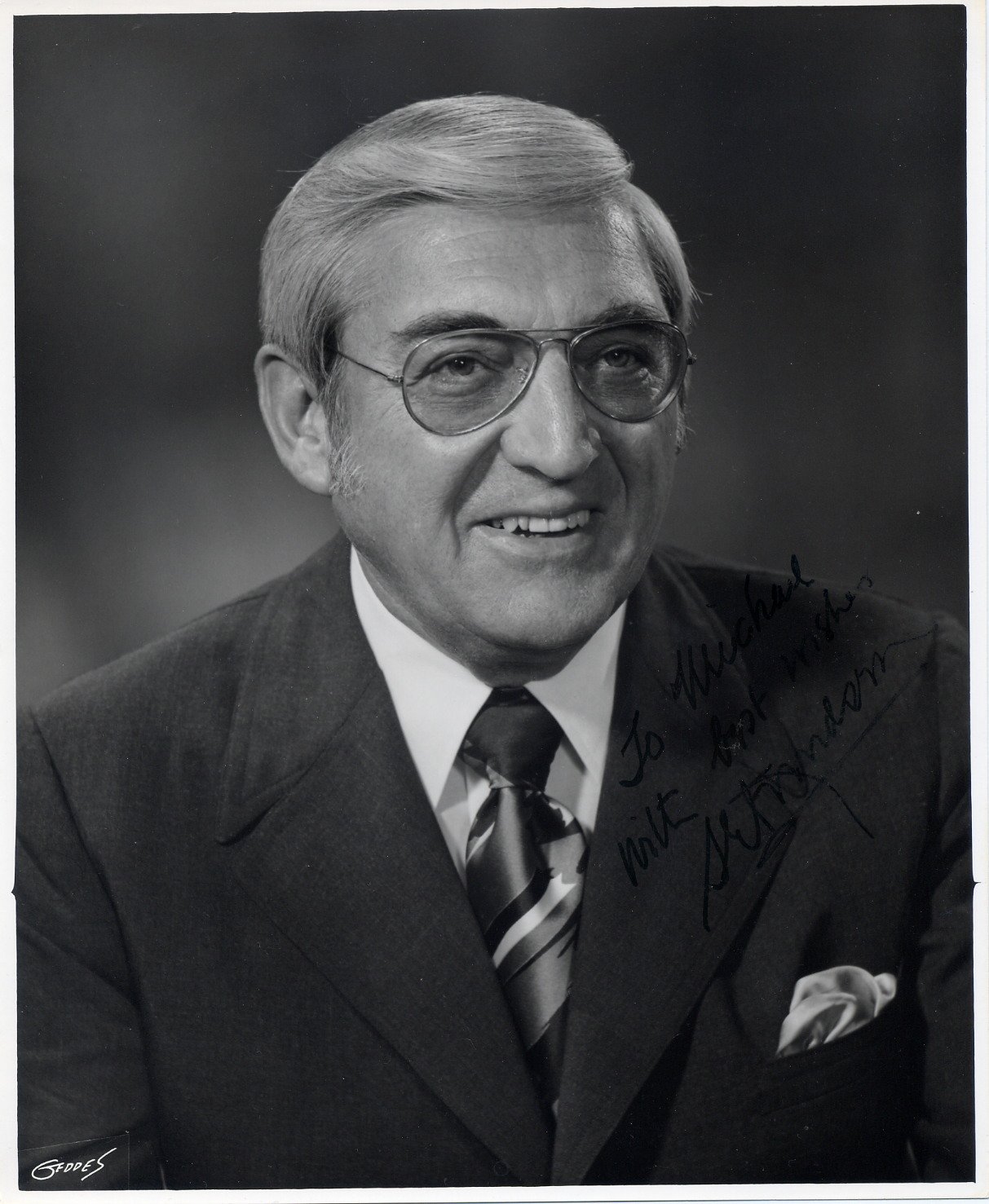

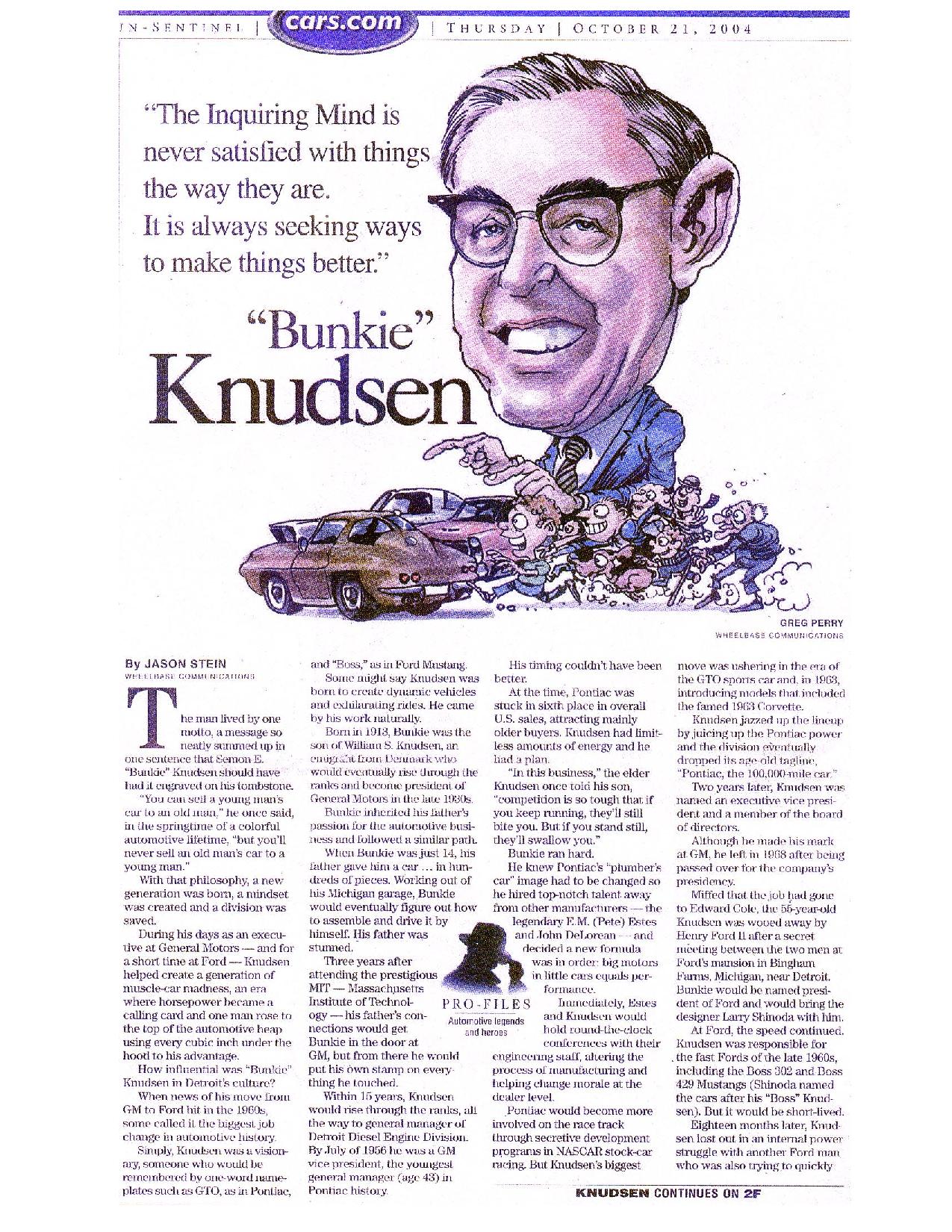

Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen from Hemmings Classic Car

I was called up to GM President Harlow Curtice’s office,” Knudsen told me back in 1994 when I interviewed him at his home in Florida. “He asked about my wife and children, and I wondered why this man was wasting his time asking about my family. Then he said, ‘Well, Bunkie, what I’d like you to do is take charge of Pontiac.’ So I said, ‘Fine, when do you want me to start?'”

That meeting in the summer of 1956 decided Pontiac’s fate for decades to come, as Semon E. “Bunkie” Knudsen became the youngest general manager in GM history at 43 years old. Though the conversation may have been concise, the road to Pontiac’s general manager’s chair and a GM vice presidency was not a short one.Born in 1912 to the son of previous GM President William “Big Bill” Knudsen (1937 to 1940–who resigned to accept a position to help the war effort)

.

Bunkie took an interest in automobiles at an early age and proved it to his father when the elder Knudsen gave his 14-year-old son his first car–in pieces. The gauntlet was thrown down in a note from Dad–“If you can put this together, you can have it,” so Bunkie did, much to Bill’s surprise.Proving his mettle to others became a recurring theme in Knudsen’s life. Though he surely had an “in” at GM through his father, he didn’t seem to exploit it.

.

B Instead, after attending Dartmouth College for one year then transferring to MIT where he graduated with an engineering degree in 1936, he worked in small machine shops. He finally came to GM as a tool engineer in 1939 and proceeded to impress his bosses over the next decade-and-a-half at GM’s Process Development Section, Allison Aircraft and Detroit Diesel. That fateful meeting with Harlow Curtice regarding Pontiac was actually the culmination of 17 years of professional effort.Incidentally, general manager of Pontiac wasn’t one of Knudsen’s highest aspirations. What we know of Pontiac’s famed exploits in the late 1950s, ’60s and ’70s was not the Pontiac of the mid-1950s. The division had cultivated a reputation for reliable, but conservative vehicles, and sales reflected it. Despite the milestone of building its six-milllionth car in 1956, Pontiac was still entrenched in sixth place, and there were rumors that it would be absorbed by Oldsmobile.Curtice needed fresh blood at the helm and a new direction for Pontiac, and Knudsen was primed for a bigger challenge on a larger stage–both men got what they sought.Pontiac public relations man and good friend, Bob Emerick, found humor in Knudsen’s promotion. Some months earlier, Bob had moved to Pontiac, and when he told Knudsen the news, ironically, he replied, “You must be crazy–Pontiac is the poorest division in the corporation!” Now it was Knudsen’s mission to change even his own opinion.He would resuscitate Pontiac by developing models with styling, performance and engineering attributes that were more enticing to younger buyers. Over the next several years, the children of the postwar baby boom would be reaching driving age. The profit potential for tapping into that youth market was enormous.Successful leaders invariably possess a keen eye for spotting talent, and Knudsen was no different. He soon recruited Elliot “Pete” Estes from sister division Oldsmobile to be Pontiac’s chief engineer and John DeLorean from Packard. Estes would go on to be the general manager of Pontiac and Chevrolet before becoming president of GM, and DeLorean would follow the same career path through Pontiac and as far as Chevrolet. To promote Pontiacs in various forms of auto racing, Knudsen worked with the likes of Mickey Thompson, Ray Nichels, Smokey Yunick, Cotton Owens, Paul Goldsmith, Fireball Roberts, Marvin Panch, Joe Weatherly and Junior Johnson.With regard to production cars, one of Knudsen’s first bold moves was to remove the “silver streak” hood ornaments from the ready-for-production 1957 models that, incidentally, his father put there starting in the 1930s. “Basically it wasn’t a bad car, but I didn’t understand why they would want to junk it all up with chrome and suspenders,” he lamented. “I told them to take all that off.”He debuted the Bonneville convertible with a Rochester mechanical-fuel-injected 347-cu.in. V-8 and bucket seats in January 1957 as a halo car to get Pontiac some attention. In February, with Knudsen’s support and the talents of Ray Nichels as mechanic and Cotton Owens’s driving, Pontiac won its first NASCAR event at Daytona. Momentum was starting to build.Despite the Automobile Manufacturers Association 1957 ban on racing, Pontiac still competed. “We got in trouble here and there, but basically there’s always a way to do everything,” Knudsen quipped. Paul Goldsmith, at the wheel of the Smokey Yunick-prepped Pontiac, won Daytona in 1958, and two additional NASCAR races were won by Pontiacs that season. A terrible recession year for nearly every automaker, 1958 saw sales sag, but market position held.The 1959 models brought an all-new lower and wider body with the introduction of Wide-Track–Knudsen had the front wheels moved out about 5 inches and the rears 4 1/2 inches from their proposed positions. Engine size was increased to 389-cu.in. from 370-cu.in., and the split-grille theme debuted. The first Pontiac fully developed under the Knudsen regime was clearly his favorite. He recalled, “The 1959 model was new from the ground up and had an entirely different look. It was wider, longer and sleeker. The chassis was completely new and used an updated rear suspension system and was much better suited to racing than the previous model. Performance options were developed and offered to the public, and they were well received.”Both the buying public and the motor press echoed Knudsen’s sentiment. The 1959 Pontiac won Motor Trend’s Car of the Year Award and posted an increase of nearly 57 percent in sales, vaulting the division to fourth place overall.Another new body debuted in 1960, and the Super-Duty racing program began to show results with seven NASCAR wins and a growing reputation on the nation’s drag strips.In 1961, the new Tempest, with its innovative half-a-389 four-cylinder engine, curved driveshaft and rear-mounted transaxle with independent rear suspension was Motor Trend’s Car of the Year–the second Pontiac to win it in just three years. The division went on to achieve third place in overall sales, and would maintain that position through 1969.By November, Pontiac had closed out the NASCAR season with 30 wins in 52 races, and Knudsen was promoted to general manager of Chevrolet. As had been the case with Pontiac, he remained a hands-on executive who delved into the styling details of his division’s cars and constantly pushed for engineering advancement. Performance street cars and a strong racing program remained hallmarks of his management philosophy.In 1962, on the production car side, the Chevy Super Sports gained popularity, and the new-for-1964 Chevelle and the 1965 full-size and Corvair redesigns were completed under Knudsen’s watchful eye. Chevrolet broke sales records in 1963, 1964 and 1965.Knudsen was promoted to group vice president in charge of the overseas and Canadian operations in the summer of 1965 and was elected to the board of directors. The next year, Dayton Household Appliance and Engine groups were added to Knudsen’s duties. In 1967, he became executive vice president in charge of all international GM operations outside the U.S. as well as of all domestic and non-automotive and defense divisions.Once he learned in late 1967 that fellow Executive Vice President Ed Cole was chosen to ascend to the presidency of GM, however, he felt his opportunity was lost. Following a meeting with Ford Chairman and CEO Henry Ford II, in early 1968, Knudsen was named president of Ford. Seeking the same sales success that he had enjoyed with Pontiac and Chevrolet, he employed the same methods–tweaking the new designs more to his liking, forwarding Ford’s strong racing program and doing things his way.However, Ford had its own system in place that Knudsen was unfamiliar with. Existing management also differed in opinion with him regarding the significance of continuing an extensive and expensive racing program. Since he didn’t bring in his own people to fill key positions, and some of the Ford executives felt they were passed over by Henry Ford II, chief among them Executive Vice President Lee Iacocca, Knudsen became an island in a deep Blue Oval sea. The respect and support earned from GM employees and management over 29 years of impressive service meant little at Ford, because in that time he had been the enemy and now he was the boss–a situation that didn’t foster loyalty.A notable exception was designer Larry Shinoda, who had gained prominence at GM with his work on the Mako Shark Corvette and the 1963 Sting Ray. He did accompany Knudsen to Ford, and both men developed the Boss 302 and Boss 429 Mustangs as well as the Cougar Eliminator.For the 1970 model year, Knudsen tweaked the Thunderbird’s front-end design, which put some Ford executives noses out of joint, and he approved a larger Mustang for 1971 that caused some internal strife.After just 18 months, in September 1969, Knudsen was ousted from Ford and replaced by three presidents, each in charge of a specific area–head of the automotive side in the U.S. and Canada was Iacocca.Knudsen’s next venture, also with Shinoda, was the formation of Rectrans in 1970, which sold aerodynamic Discoverer 25 motor homes built on Dodge truck chassis through select car dealers beginning in 1971. Rectrans became a division of White Motor Corporation, a truck company in Cleveland shortly thereafter, and Knudsen became its chairman. Shinoda also moved to White, but left to start his own design firm in 1975. Knudsen remained at White until his retirement in 1980.When I met Bunkie and his wife, Florence, for the High Performance Pontiac magazine interview at his West Palm Beach, Florida, home in 1994, both were cordial, and Bunkie was pleased to speak of the highlights of his career at Pontiac. At the time, Florence’s daily driver was a 1994 Trans Am.Little did anyone know that just two years later, Florence would pass away and two years after that, on July 9, 1998, Bunkie would succumb to congestive heart failure at the age of 85.Bunkie Knudsen left a legacy of a youthful performance image at both Pontiac and Chevrolet, and the development of a few legendary Fords, not to mention the production of a forward-thinking motor home. Thus, devotees of these GM and Ford models of the 1960s can trace their admiration to the man who said, “You can sell a young man’s car to an old man, but you can’t sell an old man’s car to a young man.”

When Roy Maloumian wants to play with his investments, it doesn’t mean shuffling funds from one retirement account to another. It means spending the afternoon cruising around in his favorite asset — an old Ford Mustang.

Two years ago, Mr. Maloumian, an Oriental-rug importer in Philadelphia, paid $40,000 for a fast 1966 Mustang. A year later, he sold it for $60,000 and put the money into a similar model from 1965 — for which he’s already received six-figure offers. The 61-year-old’s pet investment strategy? “I look for cars that I wanted but couldn’t buy when I was 20,” he says.

INVESTMENT-CAR INDEX

See our rating of 50 collectible cars, from Model A’s to Lamborghinis, including photos.

With many Americans struggling to find returns of 6% or 8% a year, a few investors are finding high yields in a different sort of investment vehicle — the cool old car. These aren’t just the Model A’s and Packards that once ruled classic auto shows, but a range of cars with climbing prices, from European sports cars to early SUVs, station wagons and even hippie-era VW buses. Some of biggest gainers are fast American “muscle cars” from the 1960s and ’70s, with prices up 70% in some cases in the past year — and rare versions of early 1970s Plymouth Barracudas selling for more than $1 million.

To some degree, new interest in old cars is a reaction to the past few years’ lackluster stock performance. But it’s also a product of wealthy baby boomers seeking out cars they could only dream of owning a few decades ago. Now, 6.7% of drivers describe themselves as car collectors, according to CNW Marketing/Research of Bandon, Ore., up from 4.9% four years ago. Classic-car sales are also growing: At the Barrett-Jackson auction in Scottsdale, Ariz., considered a market barometer, sales totaled $38.5 million this year — up roughly 40% from levels of the three previous years. And so far in 2004, Barrett-Jackson and two other top auctioneers, Christie’s and RM Auctions, say 193 cars have sold for $100,000 or more, up from 154 for all of last year.

So what’s the next big investment vehicle? To help make sense of the market, we sorted through hundreds of models collectors are interested in and put together our own list of 50 investment-grade cars from Model A’s to ’80s Ferraris. We focused on those common enough to show up at sales and auctions, and tracked each model’s return over the past five and 10 years, using data from the National Automobile Dealers Association. Then, we talked with dozens of experts, including car-club members, appraisers, restorers, insurers and museum curators, to see which cars look likely to appreciate — and which may have already peaked. With their insights in mind, we awarded each model a “buy,” “hold” or “sell” rating.

The result was a snapshot of a market in flux. Interest is waning in the cars long considered “classics” — the Duesenbergs, Packards and other luxurious cars from the years before World War II — in part because fewer collectors are now alive who remember these expensive and seemingly unattainable cars of the ’20s and ’30s. Now that boomers are driving sales, the focus is on postwar autos. Collectors are restoring and showing not only models from the 1950s and 1960s but also cars as recent as 1980s Ferraris and DeLoreans — and as quirky as 1970s AMC Pacers and Ford Pintos.

$2 Million ‘Cuda

Most of all, collectors are swarming to muscle cars. These midsize American cars trace their roots to early ’60s grocery-getters like Chevrolet Impalas and Dodge Darts. By the middle of that decade, makers had started offering big engines as optional equipment — Pontiac executive John Z. DeLorean famously stuck a huge engine into a 1964 Pontiac Tempest and called it a GTO — giving way to a generation of fast Chevrolet Camaros and Plymouth Barracudas.

Now, rare versions of Chevy Chevelles and Ford Mustangs that came from the factory with the most powerful engines and top options routinely fetch more than $100,000. Even versions of cars that were mass-market family transportation when they were new are seeing price run-ups, with show-condition 1969 Dodge Dart GTS convertibles now going for $17,000 — up about 70% in the past year. At the very top of the muscle-car market, some cars are changing hands for well over $1 million.

Bill Wiemann paid $2 million this summer — believed to be a muscle-car record — for a rare version of a 1971 Plymouth Barracuda with a big “Hemi” engine and a convertible top. Mr. Wiemann, a 42-year-old construction-company owner and real-estate developer in Fargo, N.D., says he knows the price for his white and black ‘Cuda seems extreme. But since only about 10 of these particular cars were made, he says, their rarity merits the price. “I don’t want to look like an idiot for spending so much,” Mr. Wiemann says. “I do think the price will keep going up.”

But a market like this may call for caution. University of Michigan economist Donald Grimes says that when the stock market and other traditional investments lag, people tend to park their money in alternatives like cars, art or wine. But because these collectibles have limited intrinsic value, their prices are by definition speculative — and become particularly vulnerable to shifts back to other investments. “When the stock market picks up, alternative investments suffer,” he says.

The collectible-auto market has seen bubbles before, most recently with European sports cars at the end of the late 1980s, when Ferrari Daytonas from the previous decade sold for as much as $1 million. (Now, they fetch closer to $125,000.) These days, some collectors worry that the same speculative fervor may have blown some prices out of proportion. Buyers are spending “stupid money” on muscle cars, says collector Otis Chandler, a former publisher of the Los Angeles Times. (His own collection of 50-plus cars includes many from the first half of the 20th century.) “I think it’s kind of a bubble.”

‘You Can Do Better’

Of course, many collectors say that making money from old cars is beside the point. Mr. Maloumian of Philadelphia says he considers his Shelby Mustang GT350 a sound investment, but the bigger point, he says, is being able to justify owning expensive toys that are fun to drive. (Mr. Maloumian also owns two old Porsches, a 1959 British MGA sports car and a 1930s Ford hot rod.) And Mr. Wiemann says he loves his $2 million ‘Cuda and has no plans to sell it. “If you’re looking for an investment, you shouldn’t buy old cars,” Mr. Wiemann says. “You can do better.”

Those who do buy cars as investment vehicles enter a complicated world. Slight variations in body style, engine size and original options can make the difference between junkyard scrap or blue-chip investment. And finding investment-grade cars is becoming more challenging as more collectors enter the market, because it’s harder to find old cars that can be fixed up cheaply and sold for a profit. Experts typically advise picking specimens that are already in top shape — that is, good enough to compete at an auto show. Otherwise, count on getting greasy, or spending $100 or more an hour for restoration work.

Richard Solomon discovered that buying a mint-condition car wouldn’t have been such a bad idea. The New York artists’ representative was primarily looking for a sharp-looking car when he bought an angular 1977 Lamborghini Countach for $80,000 early last year. But he was also hoping it would appreciate in value. The car needed work, and over the next year he spent more than $20,000 to recondition the engine, transmission, brakes and suspension, and he says it would take another $50,000 to get the car into perfect shape. For now he isn’t spending the money, given that a top-condition model goes for $100,000 at best. “I’m still behind the eight ball,” he says.

In general, collectors agree to pay for some combination of rarity and aesthetic allure. Take the Ferrari 275 GTB, a mid-’60s two-seater with a curvy body, cartoonishly long hood and howling 12-cylinder engine. (Walter Matthau drives one in the 1970 movie “A New Leaf,” and a convertible version appears in 1968’s “The Thomas Crown Affair.”) Ferrari made about 750 of them from 1964 to 1967. To the casual observer, the models all look pretty much the same — and a modern Honda Accord could leave any of them in the dust at a stoplight.

Yet subtle differences can swing these cars’ prices by hundreds of thousands of dollars. The first question collectors ask about a 275 is whether it’s a “two cam” or a “four cam.” Those with four-cam engines — if you’re shopping for one, pretend to know what this means — go for as much as $450,000, twice what a two-cam fetches. Three carburetors or six? Six are better, adding $25,000 to the price tag. There are short-nose and long-nose versions, with long noses carrying a $25,000 premium. It doesn’t end there: The company also made 12 “competizione” models with light alloy bodies that sell today for $1 million to $1.5 million, and three Le Mans race cars that one guide currently lists at $5 million.

The ‘Starsky’ Effect

While collector interest in certain cars may wax and wane, a few leading indicators suggest that a particular model could be poised to take off. Earlier this year, a film based on the 1970s TV series “Starsky and Hutch” put the 1976 Ford Torino in the spotlight, and on eBay Motors, a couple of them changed hands for around $20,000 — three times what people were paying a year before. Old cars can also benefit from the buzz surrounding the release of a contemporary namesake. By the time BMW began selling its updated Mini Cooper S in 2002, for example, prices for original 1960s Minis had risen to about $19,500, up 56% from three years earlier. (Minis may also have benefited from appearances in 2002’s “The Bourne Identity” and 2003’s “The Italian Job.”) This year, the best models are selling for more than $22,000.

Old Chevrolet Corvettes may be getting a similar boost right now. Donna Sandoval of the National Corvette Owners Association says the market in old ‘Vettes has “been hot” since January — which happens to be when Chevrolet unveiled its redesigned 2005 Corvette at the Detroit Auto Show. Mike (aka “Corvette Mike”) Vietro, a restorer and dealer of vintage Corvettes, based in Anaheim, Calif., says collector activity saw a similar jump in 1997, the year of the last Corvette redesign. “The new car definitely has rekindled interest,” he says.

Yet even in a rising market, some cars appear to be stuck in low gear. Edward Geller figures his vintage Italian sports car should have everything going for it, with its shapely look and engine designed for racing. The retired accountant in Morristown, N.J., says that over the years, he’s repainted his low-slung blue car, rebuilt its V-8 engine and reupholstered the interior. Still, it isn’t a Ferrari with a quarter-million price tag — but a 1973 Alfa Romeo Montreal he could probably sell for about $16,000, about the same price as a new Hyundai Sonata.

“There’s no way I’ll ever make money on this car,” Mr. Geller says. But it hardly matters, he adds, because he thinks he has the coolest-looking car on the road. “Why sell a car you love? I’d probably wind up buying another one anyway.”<table>

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

88 – 89 The McKinsey Quarterly 2005 Number 3

The open-source world isn’t the only niche community where this kind of learning and innovation now take place. The world of rare books, for instance, has been turned upside down by Amazon’s ability to aggregate the offerings of many local special-interest sellers; customers are no longer constrained by the quirky collections of titles assembled by owners of antiquarian bookshops in our-of-the-way physical locations. In extreme sports such as surfing and windsurfing, participants increasingly innovate and cocreate new offerings, such as footholds on windsurfing boards to enhance wave jumping. And customized cars, or hot rods – automobiles modified to suit individual tastes – rank among the fastest growing segments of the North American automobile market. In each of these cases, consumers are becoming more engaged in the creative and commercial processes.

Cocreation is powerful engine for innovation: instead of limiting it to what companies can devise within their own borders, pull systems throw the process open to many diverse participants, whose input can take product and service offerings in unexpected directions that serve a much broader range of needs. Instant-messaging networks, for instance, were initially marketed to teens as a way to communicate more rapidly, but financial traders, among many other people, now use them to gain an edge in rapidly moving financial markets.

The hottest 25 collector cars this summer (2018 edition)

The red-hot popularity of trucks and SUVs has been going on for so long that Hagerty Auction Editor Andrew Newton has resorted to using a nautical analogy to explain it: “High tide raises all boats.”

High tide indeed. It’s more like a tsunami.

Two generations of Chevrolet C/K Series trucks (1960–66 and 1973–87) remain tied for the No. 1 spot in the newest Hagerty Vehicle Rating, which tracks vehicles’ performance relative to the rest of the collector vehicle market. And just when it seemed we’d seen everything, the top 10 placeholders are trucks and SUVs, while another is tied for 11th. Fourteen of the Top 25 are trucks and SUVs.

“It’s one large segment of the market that has consistently seen broad value and interest growth,” Newton says. “Since trucks were cheap for a long time, they’ve had plenty of room to grow, and even as they’ve gotten pricier they remain affordable for the most part. I think that’s why the growth has been sustained.”

The Hagerty Vehicle Rating is based on a 0–100 scale. A 50-point rating indicates that a vehicle is keeping pace with the market overall. Ratings above 50 indicate above-average appreciation, while vehicles below a 50-point rating are lagging behind the market. The rating is data driven and takes into account the number of vehicles insured and quoted through Hagerty, along with auction activity and private sales results. The HVR is not an indicator of future collectability.

The top four vehicles are identical to the last HVR. The 1960–66 and 1973–87 Chevrolet C/K Series trucks each have 97 points, followed by the 1966–77 Ford Bronco with 96 and 1955–59 Chevrolet trucks with 95.

Five vehicles are tied for fifth with 94 points apiece: 1946–55 GMC New Design Series pickups, 1947–55 Chevrolet 3100 trucks, 1955–83 Jeep CJ-5, 1967–72 Chevrolet Suburban, and 1973–87 GMC C/K Series pickups. The 1973–91 Chevrolet C/K Blazer is 10th with 93 points, and the 1973–91 Suburban is tied for 11th with 92.

The first four passenger vehicles are all Japanese sports cars. The 1986–92 and 1993– 98 editions of the Toyota Supra broke into the Top 25 the last time around and remain strong, tied for 11th with 92 points. They are followed by the 1992–2002 Mazda RX-7 (91) and 1977–81 Toyota Celica (90). The 1984–89 Toyota MR2, eighth last time, slipped slightly but still carries a solid 78-point total.

“Japanese cars have been getting more attention for several reasons,” Newton says. “They’re typically newer than most vehicles we tend to think of as ‘classics,’ but many are still old enough for nostalgia to kick in. A lot of the neat cars that were coming out when Gen Xers and Millennials were growing up were Japanese. Buyers seem to be placing a higher priority on reliability in a collector car, and the Japanese cars certainly have that going for them when well cared for.”

The top-ranked American car is the 2004–06 Pontiac GTO, which is tied for 16th (89), primarily due to high quoting activity and a rise in Hagerty Price Guide values.

The most expensive car in the Top 25 is the 16th-place 1986–92 BMW M3, which carries an average HPG value of $63,600 in #3 (Good) condition. The average value of a vehicle in the Top 25 is $15,232. Toss out the BMW M3 and the average value falls to $13,217. Affordability plays a key role, as 16 of the Top 25 vehicles carry an average value of less than $15k.